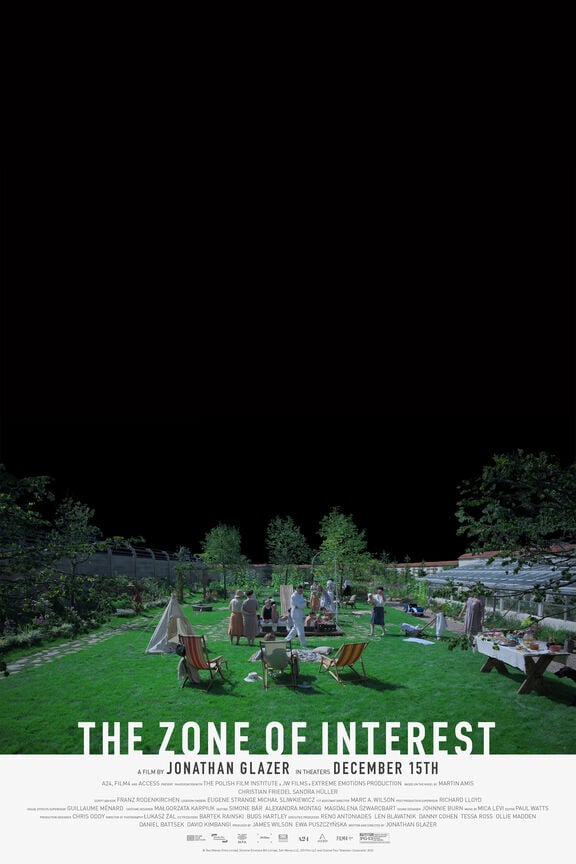

The Zone of Interest

2023 | movie

DoP Lukasz Zal

Director Jonathan Glazer

Leitz lens M 0.8

Camera Sony Venice, Sony Rialto

Production Companies A24 | Access Entertainment | Extreme Emotions | Film4 | House Productions | JW Films | Polish Film Institute I Silesian Film Fund

Distribution A24 I Bac Films I Cinéart I Diamond Films I Elástica Films I Empire Entertainment I Filmcoopi I Gutek Film I Leonine Distribution I Madman Entertainment I Madman Films I Spentzos Films I Alambique Filmes I Amazon Prime Video I Apple TV+ I Blaq Out I Cinemax I Falcon Pictures I HBO Max I Impact Films I KlikFilm I Leonine Distribution I Madman Entertainment I Max I Mubi I Wanda Visión

Awards Won 2 Oscars. 71 wins & 185 nominations total

Country UK | Poland | USA

LUKASZ ZAL, PSC CAPTURES THE ZONE OF INTEREST WITH LEITZ M 0.8 LENSES

The Zone of Interest is a film written and directed by Jonathan Glazer. Photographed by cinematographer Lukasz Zal, PSC, the film showcases a novel approach to World War II stories and makes unique use of modern cinematography tools to capture the actors just a few hundred meters from the real Auschwitz concentration camp. The Zone of Interest premiered at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival.

Seth Emmons: Tell me about the story. It’s based on a novel, right?

Lukasz Zal, PSC: The story draws its inspiration from the novel A Zone of Interest by Martin Amis and was brought to the screen by Jonathan Glazer, who both wrote the screenplay and directed the film. It gives a look into the life of Rudolf Höss, who was the commandant of the Auschwitz concentration camp and is responsible for killing almost 1 million Jews. Höss lived with his wife and three kids in a house just outside the camp. His garden was right against the wall of the camp.

The main focus of the film is Höss and his family. Amazingly, they created this kind of little paradise. They had a garden with roses, a little fountain, a greenhouse, and a dog. They would go walking in nature, swim in the lake, ride their horses, and celebrate birthday parties. He loved his family and they led their life just like you and me.

All of this took place just a few meters from where he was sending people to death everyday. Höss would say goodbye to his family, walk 50 meters to the camp gate, and spend the day completely insensitive to killing hundreds of thousands of people. His great stress in life was that he couldn’t find a solution for killing more people faster. He was just a man of average intelligence who treated his work like we treat a job at a normal business, except he was a ruthless killer.

The film presents this story with a determined objectiveness and without verbal or visual commentary, which is very unusual. You know what is going on, but you don’t see it. In a way it is like watching the CEO of a big corporation.

Did you shoot in Poland?

We did. We shot in Auschwitz in a house that was only 300 meters from the real Höss house and the camp. We couldn’t get the real house, but we found a similar one nearby and Chris Oddy, our production designer, researched lots of archives and pictures to partially rebuild and redecorate the house and the garden.

We placed a large green screen behind the house so we could add the camp into the background. During the film we see that there’s a camp, we see him going to work and crossing through the gate, but we never get into the camp. We do see prisoners working in the garden but not in the camp.

What is the motivation for not showing the camp and prisoners?

When we were prepping the film Jonathan told me he wanted to create an experience for the audience similar to building a scaffolding of images and sounds beyond the frame that would allow the viewer to imagine and fill in the gaps in their own mind, rather than showing everything explicitly on the screen. That can create a very powerful experience, especially with a subject that has been shown so many times on film and television.

We wanted to avoid being overly emotional or manipulative with our shots and framing, which took some time to adjust to. I remember once Jonathan and I were looking for frames for a scene that shows a character before he ends up being killed. I found a very nice frame with an intimate camera position and Jonathan said that if we show him like this, so close and emotional, and then he’s killed in the next scenes it will be manipulative of the audience. In any other film that would be the goal, but here we wanted to do the opposite, so instead we did a simple wide shot of the character standing and looking through a window. That’s it.

We just wanted to be as unaesthetic and objective as possible, not manipulating the audience emotionally, not adding any drama with the camera or any special look. We didn’t want the audience to feel anybody behind the camera, so we really only moved the camera when there was a reason to do it.

What references did you and Jonathan use to discuss and develop the look of the film?

Honestly, there was no reference for this because we had not seen a film that looked like what we wanted to do and everything we did was completely against the rules of filmmaking. We did look at some images of natural light because we used so much natural light, but then we would shoot in the middle of the day, at 12pm or 1pm in the heat with ugly front light and shadows on the faces. In terms of production design, you would never paint a house in these colors, which were historically accurate but close to skin tones. We also avoided beautiful locations and just focused on what was around the Auschwitz area.

The most important rule of the film was to be as close to the truth as possible. We used the same light bulbs they had in the 40s. There were blackouts at this time because they were afraid of bombings so at night it is dark outside with maybe one bulb on the shed or house. Even the camp is not visible at night. We only used practical lights, no reflectors, no flags, no fill.

How did you approach capturing the film from a camera perspective?

To remove any feeling of a camera operator or outside influence on the set we used 10 unmanned cameras at one time.

Ten cameras?

Yes. We would hide the cameras in cupboards, in the corner of a room, or outside and run cables for playback and control. There was no crew on set and only the most minimal film equipment. We drilled holes throughout the house so we could run the cables without being visible. We wanted to create a kind of real life inside this house to give the actors the opportunity to act without influence or distraction. We used Sony VENICE cameras with the Rialto extension system to make the smallest footprint possible and still have control.

How did you manage all this?

Behind the camp wall green screen we had a large shipping container setup for playback and would hide there and watch the action. Jonathan would be in there as well. The focus pullers were in the basement of the house with monitors. Everything was hardwired. There was no guarantee that this many systems would work with wireless playback, WCU, etc. so we decided not to use any Teradeks at the house.

We would roll for as long as possible before changing cards. We shot using Sony’s X-OCN ST compression at 6K 3:2 aspect ratio. When it was time to change cards we would often remove the actors first so they didn’t interact with the crew to maintain the authentic feeling for them. When we were doing our setups we only used stand-ins for the same reason.

What was the process of setting up your shots like?

It was a very strange and difficult process, but always the same. The camera department was a commando team of about 20 people: one camera operator, three grips, between five to seven 1st ACs, five 2nd ACs, two DITs, and two or three playback operators. We had some special Riedel communicators with lots of channels so we could have constant communication with the different departments on their own channels. Communication was so necessary when setting up 10 different cameras.

Depending on the scene we would use a mix of wide shots, medium shots, and sometimes close ups. It was a long process and we usually only did two setups each day. I would prepare a camera position plan for the day with the floor plans of the house and garden and in the morning we would come in and start looking for frames.

For me the composition of the frame is the most important thing. Sometimes you just move the camera a bit, a bit lower, a bit to the right, and it changes everything. I don’t like to feel the camera. I just want the viewer to be immersed in the situation.

We would choose the lenses, set up the cameras, walk back to the monitors, and the first look was always a disaster. Not all of them, but on the first attempt more than half of the shots wouldn’t look good. I would point to different monitors and say, “Number five is great. Seven is great. Two is okay. Three is terrible. Six is garbage. Nine is a disaster!” We would walk back around the wall, move this camera, lower that one, change a lens focal length here, and it still wouldn’t work. Then do it again and again. By the end my brain would be boiling from so much information. It was a really long process and always terrible at the beginning, but eventually all the frames would look good. I had an amazing crew, but it was a crazy process because we had never done anything like this before.

What was it like pulling focus on 10 cameras without firm direction and blocking?

Because of how we set up the cameras, each focus puller would be responsible for two cameras. Usually one would be simple, like a wide shot, while the other would be more complicated. And those two cameras would usually be in different rooms or different places so as the characters walk from one room into another the focus puller is switching to the other camera.

This sounds like a crazy set. When you were preparing for this film, what was your lens search like? How did you come to choose the Leitz M 0.8 lenses?

In my first zoom call with Jonathan Glazer and Tom Debenham, who was a sort of visual effects supervisor on the film, I said I thought we should use the Sony VENICE cameras with the Rialto extensions to be as small as possible. Now we needed small lenses to match. We didn’t want to just choose the smallest lenses we could find so we tested a lot of different lenses, new lenses, old lenses, everything.

I had never worked with Leitz lenses on a film, but I used to shoot still photography with a Leica M6. I really loved that camera and the M lenses, but I thought maybe Leitz would be too clean and too sharp. Jonathan liked the idea of shooting this movie with German lenses so made sure to test all the German lenses in the market too.

We shot a bunch of lens tests at Panavision Poland with a person in frame in natural light and when we watched the tests we realized that although I love vintage lenses, especially on digital cameras, they wouldn’t work for this film. Same with anamorphic. We didn’t want to impose a look and felt that those lenses did too much in that way.

I was surprised by the Leitz M 0.8 lenses. They were sharp but they had the objective look we wanted. And they were small and fast. After watching the tests we said, “Wow, these are the best choice for us.” We ended up with five full sets of the lenses on this film.

I tested them with some diffusion filters because I was still afraid they might be too sharp, but I quickly fell in love with the clean, cinematic look of them. They’re not clinical though, they have a tint of vintage feel to them. Some of the new large format lenses feel almost medical because they are so perfect. But the M 0.8 lenses are not so perfect. At T1.4 they are very sharp in the middle but a bit blurry in the corners. We were composing in the center so it worked well for us.

They also worked very well in the night scenes with candles, oil lamps, and practicals because they aren’t very flarey. Sometimes there would be sun coming in the window directly into the lens. I remember Jonathan came to me once and said, “Lukasz, I’m looking at these images and it’s very striking to me. These lenses are sharp, but they have something else. They don’t impose any look, but they have this little bit of softness.”

They were very kind to the actors and had great definition, but also this very discreet charm. As I said, I like vintage lenses, but I don’t like using them for cheap tricks when you use the lens to do that work instead of building the look with other tools. I like the kinds of lenses where you need to compose well, build your picture, and the lens is helping you but not doing your job for you or talking over your other work.

In life we are surrounded by very effective, attractive, beautiful images and sometimes I think this is kind of boring. We filmmakers have so many tools now, so many amazing cameras, and it’s easy to create an attractive, beautiful image, even in almost no light. But I like images to be raw and modest and not use all the tricks because I think that power of the image sits in the contrast, in the composition, in how you place the person, in the production design, but not in an attractive way. I’m trying to avoid these easy attractions. These kinds of lenses work really well for me because they don’t impose any strong thing on the image.

Were there any aesthetics or choices from your film Cold War that informed parts of this film?

Not really. In The Zone of Interest we tried to be completely unaesthetic and objective. We kept our frames very geometric and used a lot of wide shots. Of course, we did have portrait shots, but many of them were more like a medium shot and included a lot of production design, so it was more like a combination of a person and a surrounding.

This kind of portrait with wide lenses is amazing to me. For example, there was a meeting of crematorium designers, a bunch of guys sitting at a table. We had the cameras just on the table close to the characters, but with wide lenses these are medium shots with the whole person in the center and the background of the room around them. It’s very geometric.

All the time we would catch ourselves looking for something interesting and remind ourselves to go back to the unaesthetic look and focus on finding a frame that is not the most beautiful but works best for the story. There was one moment when we were shooting in a real concentration camp in a gas chamber with two cameras and I remember my camera operator Stachu Cuske asked me, “Lukasz, do you like this frame?” It was 5 o’clock in the morning and I just stopped and thought, “What are we doing here? How can you make a nice frame in a gas chamber?”

But that is exactly what we were trying to keep in mind for every shot, for every frame. No to be aesthetically driven, not to look for attractions, not to look for nice frames and nice light. Just be objective. It’s so different. I’ve never seen anything like this before.

What focal lengths did you use regularly?

We were mostly using the 28, 24, and 21 mm. Sometimes the 35 mm, but mostly the wider ones. I think the 24 mm was my favorite. The 21 mm has a bit of distortion on the edges, but we used all the wide ones. We also had two Angenieux zooms, a short and a long, but most of the film is shot on primes. We rented the equipment from Non Stop Film Service in Warsaw, which is part of the Ludwig Kameraverleih rental group in Germany.

Did your previous work in documentary help you or inform any of the work you did on this film?

I use my documentary experience all the time in my work and especially on this film. When shooting a documentary you need to anticipate where things are going to happen and get the camera in position to capture it. Also, you need to have your eyes open all the time and be able to improvise because there could always be a better solution or a surprise happening.

Whenever we were setting up the cameras we were using stand-ins, but actors were helping us as well, and we didn't know exactly where the actors would land or meet each other or sit and talk. We had to anticipate all of that. Sometimes they would be told generally where to go, or one of the actors might have some idea where to go but not all of them, so we had to be ready for anything. Our main actors were professionals, but many of the others had not acted before. This also made things less certain. All of these were reasons why we would frame a bit wider.

What was the motivation to use non-professional actors and shoot this way with minimal involvement of the crew and the director?

We wanted as closely as possible to capture a piece of truth between people. That’s also why the 10 cameras were necessary. The non-actors would never do the same thing two times in a row, so with all the cameras we could capture each scene with consistent weather conditions and acting and it feels more real in the edit.

Jonathan created the conditions to capture in this unique style. Everything is transparent when you have 10 cameras shooting together and you don’t feel like there is a person putting their stamp on the image. We were creating a container and capturing a piece of life.

I’ve heard you say before that working on a film is like going on a personal journey and that you’re often aware of how it changes you mentally and emotionally. Can you speak to what that journey looked like on this film?

This film is very special to me and was an amazing experience, but it was very tough emotionally. Every day going to set I would pass Auschwitz and our location was just a few hundred meters away. Being there brought up some very tough emotions. The whole story itself was also difficult emotionally.

From a cinematography perspective this film changed my thinking about light. In the beginning I was afraid of using just natural light. Then I tested the most extreme exposure setups in terms of sun in the frame, being in the house, etc. and began to convince myself and fall in love with natural light. I see myself using less lighting equipment in the future. Sometimes it’s so great to just turn it off and shoot interiors with just one bulb. It was great shooting with candles and oil lamps, or with one practical in a house or a whole stable.

We wanted to be very real, and it’s so funny that now I watch films and see four practicals in a room and think, what is this? This is so unreal. You don’t have to have everything in light. You can leave things in shadow. You can limit yourself, reduce things, and just really observe. I am looking now for a good and proper light in the scene, not a beautiful light.

I learned that sometimes light at 12 o’clock or 1 o’clock or 3 o’clock could be amazing. If you really embrace it then it can look amazing as a front light. You see the sweat on people’s faces and you feel the heat transferring to the image. It felt so amazing to be really open not to beautiful things, but to things that worked beautifully for the film. It was an amazing lesson for me in terms of being really bold and not using lights.

And really, this whole story is such a universal story about us as human beings. You see this person who has a normal family life and you discover that he’s really a monster, but then you start to understand that it’s really about us and that it is in some ways universal and we are all beautiful and terrible. These are important stories to tell and I feel really privileged to participate in this film and help Jonathan tell this story.

Overview

DoP Lukasz Zal

Lens used

M 0.8

Legacy

Unique and small. A new way to look at light, skin and color.