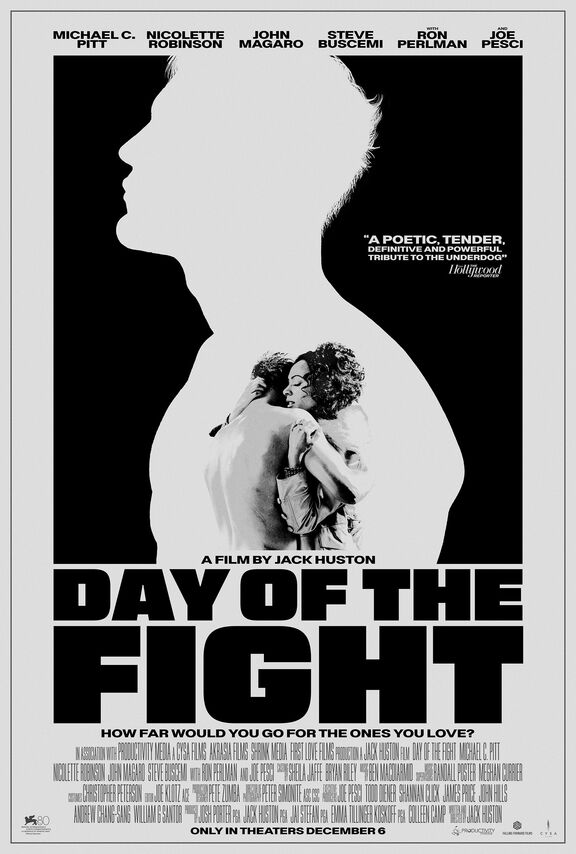

“DAY OF THE FIGHT” IN BLACK AND WHITE WITH PETER SIMONITE, ASC, CSC

Day of the Fight is the directorial debut of actor Jack Huston and premiered at the Venice Film Festival in 2023. Filmed by Peter Simonite, ASC, CSC, the film follows a boxer on the day before his first fight after getting out of prison and endeavors to capture the emotional complications and complex relationships of one man’s life over the course of a single day.

Seth Emmons: Tell us a little bit about Day of the Fight.

Peter Simonite, ASC, CSC: On the surface, it’s a boxing film set in 1980s Brooklyn, New York, but it’s not the boxing film you would expect. It’s a day in the life of a fighter who is preparing for his big comeback bout while he’s tying up loose ends with his loved ones. Throughout the day his backstory is revealed bit by bit and you see what a hard life he’s had up to this point. It’s a quite emotional and vulnerable story, more On the Waterfront than say Rocky.

We screened a bunch of movies in prep. La Haine was one we watched particularly because it has a lot of oners in it and Jack wanted a similar uncut feel for parts of this film. We also looked at some of his grandfather Jack Huston’s films, particularly Moulin Rouge, which has a really interesting treatment of color and became a touchstone for us. Day of the Fight is primarily black and white, but there are some scenes in color.

Jack felt that many of the black and white movies to come out recently have a softer grade to them, which he wasn’t too keen on. We went for more of a silver gelatin print look, a more classic look. We looked at a lot of street photography and the goal was to make it feel like a photographic print and less like a creamy image. There are some scenes that take place in his memory that have a hint of color to them, almost a hand-tinted feel.

Technically, how did you go about shooting for this look?

I chose the ARRI Alexa 35 initially for its size and dynamic range. During testing we looked at the in-camera black-and-white LUT and Jack responded to it immediately. We tested some other options but decided that shooting in color with that LUT was the way to go. We decided to shoot in color and used the LUT as a starting point to fine tune the black and white during grading with Tim Stipan over at Company 3. In the film there is a lot of significance to color and when it is applied, and it was nice to be able to key certain colors and set the values differently.

Tell us more about the camera and lens choices for this film.

The Alexa 35 gave us a very rich format regarding dynamic range that could save highlights and reach into the blacks. In the grade it all came out looking so natural. We paired the camera with the Leitz SUMMILUX-C lenses. Initially we considered going with vintage lenses since it is sort of a period piece, but Jack and I thought of the story in more classic terms and the Summiluxes have a very classic look. There’s something about the Leitz lenses that is so timeless and Jack’s grandfather’s movies that we were referencing also have a timeless look to them.

There’s also the connection to Leica’s history of street photography that comes into the look of the lenses. Day of the Fight has that kind of eye like a street photographer with a Leica M3 and a fixed lens. When we put them on the Alexa 35 with the black-and-white LUT we knew right away this was the look of the film.

On the practical side of how we worked, the lenses fit well because they’re pretty small, all match in size and T-stop, and they handle flare really well. We did a lot of oners on this film and our Steadicam operator Jim McConkey and 1st AC Anthony Cappello felt that a set of smaller, consistent lenses would work better for the kind of moves we were going to do. We’re passing through spaces and handing off the camera at times. The small camera and lens combo worked beautifully for those types of moves. It’s nice when the operators and assistants are happy with the gear.

Oners can be fairly challenging. How was it on this film?

Actually, it was pretty incredible. We had such a great team. As it happened, The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel was just wrapping as we were prepping. I reached out to Jim [McConkey] and sent him the script. Jim is the best of the best at moving the camera. He has impeccable instincts, perfect timing, and a rich love of cinema, and I knew he would be a great collaborator for our project. He was really enthusiastic about the film and brought his team from Maisel on board, including Anthony Cappello, B camera operator Niknaz Tavakolian, and key grip Charlie Sherron.

It was important to Jack to have an improvisational element to the production and to prioritize performance. Generally speaking, oners require time and rehearsals, but Jim, Charlie and Anthony were able to pull things off often on the first and second take that I wouldn’t have thought were even possible.

When you have a crew like that with so much experience working together, how do you fit in your language to their already-established shorthand?

Their shorthand and familiarity with each other was invaluable to us. It’s hard to quantify how much they improved the project because of how well they worked together as a team. On day one of shooting our AD who had been with the project since the beginning was out with covid, so we had a brand new AD. But when I think back to the energy and excitement of that first day on set, having a rock solid team that was able to move quickly made our first day shooting together such a success. We started off on a high note and they brought that level of expertise and professionalism every day.

In terms of establishing a style and language with the team, it was never an issue because they’re all artists. Jim and the whole team were fully invested in the story. We had many conversations about what we were going for and how we wanted to work and they adapted to that without hesitation. When you work with people who are that good you also want to make sure that their voices are heard. If they had an idea about how to accomplish something that worked for the scene then we incorporated it. Plus, Jack is a great collaborator and knows how to work with a team like that. It was just a big, happy family. I learned a lot from Jack and Jim that I will carry on with me.

One of the reasons the crew was so important is that Jack really envisioned this as an open experience for the actors so we played it a little looser to allow for improvisation and not get in the way of the performances. We weren’t necessarily blocking and staging or covering things in a traditional way. It was very reactive, which is more demanding on the crew because you have to think and adapt on the fly.

How did you prepare to create that freedom of movement?

We knew that in many situations we would need either a 360° set or at least 270°. The key to that was location scouting with Jack, production designer Pete Zumba, and producer Josh Porter to make sure all our locations would be immersive so that we could look in any direction, there would be windows or natural light, plus photographic depth to look into.

How did it affect your lighting choices?

It definitely changes the way you light and placement becomes very important. We started with the locations and then added accents out of sight. There were times we had to scramble to hide something, but I love how it forced us to develop a unique style for the film that I feel gives it a kind of authenticity.

Callum Shaw is an incredible gaffer and brought a real freshness to the lighting approach. We used a lot of ARRI SkyPanel S60s, Astera Titan tubes and Jokers. Negative fill was a huge asset, as well as being able to turn things off wirelessly on the fly. We used 18K HMI fresnels to light the church and M18s for the shaft of light effect. For the Madison Square Garden scene we used a soft top source with some direct pars hitting to give a very authentic look even though we weren’t really at the Garden.

You’ve worked with some legendary cinematographers during your career. What is something you learned along the way that has shaped the way you work on a daily basis?

Working with Chivo [Emmanuel Lubezki] and [Terrence] Malik on The Tree of Life and To the Wonder changed my life and how I work. It was a very improvisational experience with this utter dedication to light. It has freed me as a photographer to be responsive to what’s in front of me rather than trying to meticulously stage everything. And, when you have a vision to really go for it.

It freed me up to do something like this film with Jack where I can have confidence in our eyes and not worry if we don’t know everything ahead of time. We knew we were setting ourselves up with these locations, this light, this time of day, and we knew that we could make something magical with that. It can be demanding on everybody else because it means the instructions in prep aren’t as specific and everyone has to roll with that approach, but we obviously had the right team for it.

It was great to work with Jack because he has a real artist’s eye for visuals. Having written the script and also bringing a lifetime of film experience working with some of the best directors in the business, it didn’t feel like working with a first-time director. He had a very specific vision and is an uncompromising artist in the best ways. He knew what he wanted and was able to speak about it fluently. I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone who was working at this high of a level on their first film.

Overview

DoP Peter Simonite

Lens used

SUMMILUX-C

Performance

Fast, compact, reliable, beautiful in color and excellent in contrast.