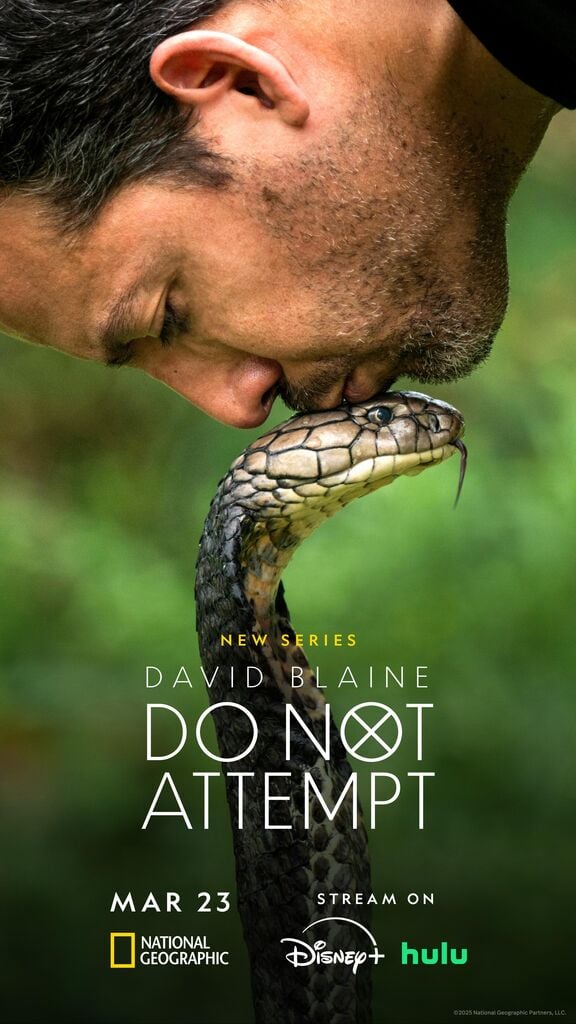

Luke Cormack Makes Cine-Magic with Leitz SUMMICRON-C on “David Blaine Do Not Attempt”

David Blaine: Do Not Attempt (2025)

David Blaine Do Not Attempt is a six-part docuseries from National Geographic and Imagine Documentaries following magician and endurance artist David Blaine across the globe in search of practitioners of extraordinary feats of magic, talent and skill that border on the impossible. Cinematographer Luke Cormack was tasked with capturing the magic and mystery of this three-year journey in a unique way and chose Leitz SUMMICRON-C lenses to help bring that vision to the screen.

Seth Emmons: What was your path into the world of cinematography?

Luke Cormack: Another lifetime ago I was a game ranger and dive master in Southern Africa taking people diving off the coast or driving them around in a Land Rover to see elephants and lions. I felt such a great peace being out in nature, but unfortunately you earn peanuts. I decided to study film and TV at the Durban University of Technology in South Africa so I could do wildlife cinematography. Those studies ignited a real passion in me for moving images. I did some wildlife and underwater work before falling more into the documentary world. Eventually I moved over into narrative, commercials, features, and now it’s a real mix, which I like. It keeps me creative and inspired. I split time between Los Angeles and Cape Town.

How did you come to work on David Blaine Do Not Attempt?

I knew a few people who were working on it that put my name in the hat and went through the interview process. I think that being comfortable working on a mix of genres helped. I also clicked immediately with director and showrunner Toby Oppenheimer. It was like I’d known him for 150 years, which was awesome because we worked so closely together for three years from the prep stages through principal photography.

Three years is a long time. Was there downtime in between episodes?

There never seemed to be enough downtime. [laughter] We would go off and shoot for about a month, then come back to get our ducks in a row with research and setting up locations and finding those incredible characters that David would get along with for the next episode. It was a lot of work and we had a great team doing it.

Tell me about the structure of the show and how you approached it.

It’s a unique series because David [Blaine] is an amazing person, but he isn’t an actor and he’s not really a host either. David doesn’t like to feel like he’s on camera, so the goal was to allow him to move anywhere and for the action to flow naturally. I refer to it as creating a biosphere of spontaneity.

A lot of our prep was picking the right place and right person for him to connect to and create a relaxed atmosphere so his genuine personality could shine. That’s why the show works so well. Prep made that possible. We scouted locations, put up lights, but everything was 360°. We were constantly at the ready and staying nimble to capture the vérité because David wasn’t looking to hit a mark. He was following his interest and intuition.

For example, at the spice market in India we had a beautiful little space setup for him to land and have a conversation, but he blew right past it and walked into the middle of the spice market. We were running after him, finding the angles, adapting all the time.

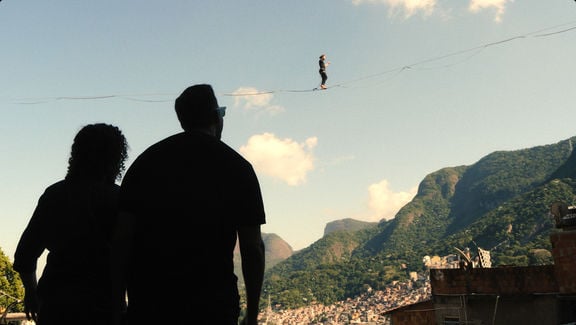

There were some big set pieces that needed to be meticulously laid out and orchestrated, like in Brazil when he was setting himself on fire. We had 10 cameras, including drones, underwater cameras, fixed cameras, handheld, everything. Most of the time though we worked in documentary style with a documentary budget, but some parts you want to feel bigger than the budget, like those set pieces.

That brings up an interesting point. Can you speak to your equipment choices and why you chose to use prime lenses as much as possible given the vérité nature of the production?

From the beginning we wanted the show to appear bigger than the budget. We had so many talks about the equipment and did tons of testing. We started with the camera and originally wanted the ARRI Alexa 35s, but they were kind of heavy and had just come out. In the end we decided to go for the Canon C300 Mark III, which turned out great. It held up well and was a bit lighter, which helped because there was a ton of handheld work. So many times it paid off to just keep the camera on your shoulder until everyone stops paying attention to it and relaxes.

In terms of lenses, we had a range. We had zooms, but I also wanted primes for set pieces, interviews and B-roll. I knew there wouldn’t be any marks or many opportunities to perfectly light something, so I wanted lenses that I knew were going to look great every time I put them on the camera. We tested so many lenses and I found that the Leitz SUMMICRON-C lenses were so flattering for the faces and everything else. They created great images no matter where I pointed them.

I’ve always loved Leitz lenses and have used them on most of the documentary stuff I’ve done in the past whenever there’s a chance to bring them in. I’ve got a real soft spot for them. I’ve used the SUMMICRON-C and even SUMMILUX-C lenses plenty of times. They’re absolutely gorgeous. Recently I’ve been using the HUGOs. If they had been available when we started I would have used them. Occasionally I would have liked the T1.5, but the SUMMICRONs were great.

We kept a pretty consistent camera and lens package. Eventually we got down to four cameras. One had the 50mm prime on all the time. The others were rigged for handheld with zooms. We brought in extra cameras for the big set pieces to get a few more angles. We also used the DJI Ronin 4D a lot, and drones too. We used Adorama in New York for most of the project and A-Frame in Brooklyn supplying some equipment as well.

This show includes a lot of crowd scenes with David mixing in with locals or performing a bit of magic on the street. What are some tips or best practices for that kind of work?

One of the biggest considerations in every scene is safety. We would walk through our locations before shooting and then do a run through with our amazing safety guy Sebastian Pot. He would go in and then give us the rundown. Knowing that he was keeping an eye on that allowed us to concentrate more on our jobs.

Some of these places like Rio de Janeiro, Johannesburg, a few others, you have to keep your head on a swivel and know what’s going on around you. Sometimes we were walking down the street in a township or favela and suddenly guys come around the corner and they’re armed. You’ve got to stop filming immediately. The number one thing is knowing your exit at all times.

Or we might be at a train station and what starts as a shot with four people around David quickly becomes 40 or 50 people. Take that extra second to see where your feet are. It’s so important to just look down every now and then. There are stairs over there, or there’s a train right next to me. You can’t just be dialed in on what you’re filming. One eye is watching framing and focus, but your other eye is looking around.

That’s also part of documentary work in general. I’m looking at the operator who is cross shooting with me. Sometimes there might be three or four. Being in communication on the walkies was super important. We were constantly communicating, figuring out when we need our wide shot, when we’ve got to back up. Or can I go in now because there’s an amazing close up opportunity? You have to go in and get your moment and then pull back. Everyone is working together organically.

As far as getting the shot in a crowd, there are a few tricks for that. Sometimes it’s just sliding an apple box under the operator’s feet and suddenly they’re up above everyone. Aputure tube lights are a great part of the kit for working in crowds. If you end up in a dark corner you can quickly pull them out and they fill in a little bit and look natural.

Also, once people are aware of the camera they start acting differently. If you’re sneaking in on a longer lens or holding a camera that doesn’t look too fancy like the Ronin, people forget about it and then you get a genuine reaction, which we were constantly after.

When David would get the cards out for a magic trick everyone crowds in and is focused, but somehow you have to get in there to get the shot. How you get that shot completely changes depending on what country you’re in. If you’re in a city like New York and you put your hand on someone’s shoulder most people will turn around and give you space to get in. Or you might be in a rural setting and people just naturally give you space. But in New Delhi, no way. You can be tapping, scratching, talking to them and they aren’t turning around. You really have to push yourself in there or get an apple box or something.

Do you see any parallels between wildlife cinematography and documentary-style work in cities and urban environments?

The biggest thing is being present. When I’m at work I’m not on my phone, I’m not doing other stuff, because the moment you need could happen at any time. That little bit of magic that you’ve been looking for the whole shoot can happen at a train station while you’re fiddling with your camera or checking your eyepiece. An amazing person walks over and David has an interaction with them. That’s the stuff you need. And you can’t recreate it. It’s the same in the wild. That cheetah is not going to do the same thing again if you ask it to.

Body language is also important. Both people and animals have a lot of tells that they’re giving away all the time. If you see a lion stalking a buffalo you have to anticipate where that kill is going to happen and put yourself in the best location to get the shot. 90% of the time it’s going to happen behind a tree [laughter], so you need to get in front of the tree.

If I can see that a person is about to take a step or two, or turn left, for example, then I can slide in front of them and now I’ve got a shot of them walking towards me. Knowing when to jump in front to get faces is crucial because you don’t want to stop the action. I might see an opportunity for a cool reflection up ahead and run up to get them passing through that reflection. You’re constantly trying to stay two or three shots ahead.

The main parallel is that once the moment has happened, if you miss it, you’ve missed it. You’re never going to be able to recreate that energy, that magic, and that’s what we’re always aiming for.

How did you balance capturing so many different locations with such different environments while remaining consistent throughout the series?

We did feel a need to keep the look consistent, and the camera and lenses helped with that, but the geography definitely changed the vibe and color. India is so warm compared to Finland, which is so blue and cold. Those differences are organic and you embrace them. We can tweak things a bit in the grade, but you allow each place to have its own magic.

We would try to highlight those elements through our B-roll shots. We would scout and find the things that would help show what makes these places tick. It could be an incredible view or some little detail on the side of a building. We would always try to bring the SUMMICRON-C lenses out for those shots to capture them as beautifully as possible. We’d do a timelapse here, a hyperlapse there, whatever we needed to do to bring the magic out.

The whole time we’re trying to highlight the texture of these different places we would be having discussions about how David might see things. What would his POV look like? We’re not just in a market trying to capture a market scene. We’re looking for a broken mirror or a reflection on the water, an unusual or unexpected way of looking at the world. We went down the rabbit hole with diopters and shooting through crystals and using different lights to get a unique take on the world because in a sense this show is trying to present the way David sees the world. We’re all unique individuals, but David’s vision is particularly unique.

David Blaine: Do Not Attempt

2025 | series

DoP Luke Cormack | Michael Richard Martin | Ethan Mills | Cristian Dimitrius | Roger Horrocks | Jeremy Leach | Kaleu Wildner | Michael Yelseth

Director Toby Oppenheimer | Matthew Akers | Abigail Harper

Leitz lens SUMMICRON-C

Camera Canon C300 Mark III

Production Companies Imagine Documentaries

Distribution Disney+ | Hulu | National Geographic Channel

Awards 1 win total

Equipment Supplier Adorama | Manhattan

Country USA

Lens used

SUMMICRON-C

Character

Premium prime lenses designed for larger sensors on film and television productions.