THE CINEMATIC PALETTE OF CHEF’S TABLE

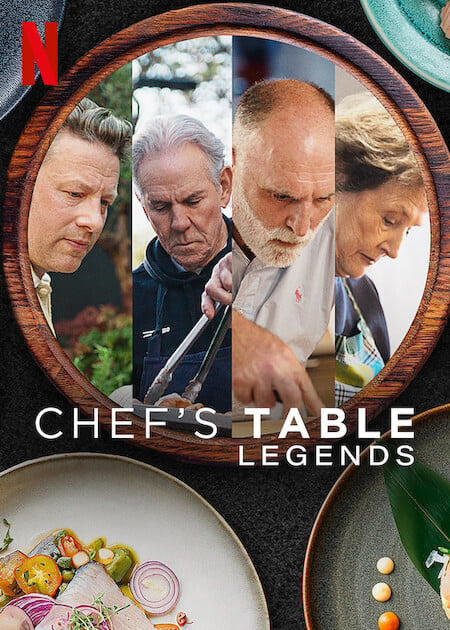

CHEF'S TABLE: LEGENDS (2025)

For 10 years Netflix’s Chef’s Table has redefined how audiences experience food on screen. It is less a cooking show and more a poetic meditation on the culture, creativity, and most importantly the humanity of those pushing culinary boundaries around the world. Cinematographer Adam Bricker, ASC and Executive Producer and Director Brian McGinn discuss the origins of the show’s look as well as the tools and techniques used to put together each episode.

Seth Emmons: How did you two get started making Chef’s Table?

Adam Bricker, ASC: Off the success of David Gelb’s groundbreaking feature documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi, David, Brian, and EP Andrew Fried sold Chef’s Table to Netflix. Brian brought me on to shoot the pilot in Melbourne, Australia, profiling chef Ben Shewry. I had almost no documentary experience and had never shot food before. As a group, we were trying to take Jiro to the next level, though we weren’t totally sure what that meant yet. But we assembled a small crew of like-minded filmmakers and headed to Australia to start figuring it out.

Brian McGinn: It’s crazy, but other than David, no one that worked on the series had any food background. We were just young, ambitious filmmakers who wanted to make narrative movies. It was a moment when cinema aesthetics in documentary storytelling was still a relatively new idea. We’d decided to take the opportunity to make something super cinematic, but we had to figure out how to do that on an eight-day shooting schedule. I think our naïveté was helpful, as was David’s trust that we weren’t going to screw it up.

What made Chef’s Table different from other food shows?

Brian: First off, on a really basic level, we had no host! Instead, our goal was to transport the audience into the emotional and mental space of each chef on an episode-by-episode basis. That meant we had to aesthetically translate what they were doing at a high production level, while simultaneously cracking the story and drawing out something intimate and relatable narratively. Again, naïveté was our ally.

Adam: We were aiming for it to feel filmic, so shooting entirely on prime lenses became a no-brainer. That choice ended up shaping the filmmaking in ways we didn’t expect. Without a zoom, we had to dance with the chef — make a decision, move to a spot — which created a much more immersive visual style. We were filming right in the middle of live service. If we’d used a zoom like a traditional doc, I think we would’ve ended up buried in a corner, just trying not to get in the way. The fixed focal lengths forced us to bring the audience into the action.

You use Leitz lenses. Why did you choose them?

Adam: The Leitz lenses are such a solid tool for our style of documentary filmmaking. They’re compact, which keeps our camera build small, and that’s helpful in a tight kitchen. All the focal lengths share the same form factor, so your focus rings line up, you’re not swapping matte box backings, and lens changes stay quick and efficient. After using SUMMICRONs early on, we were so happy with the quality of the image that Brian and I bought a set that we still use to this day.

Brian: Because we were lucky to be early in the wave of this new, cinematic documentary filmmaking style, Adam and Will [Basanta]’s work with Leitz lenses has come to define a kind of “premium documentary” look. And of course, our passion for the Leitz/Leica look extends into our personal still photography. For a while Adam and I were shooting with Leica Q cameras, then moved on to Leica M10-R’s. Now I’m on an M11 and he’s picked up a black paint M-P. The trademark Leica look has really defined both the show and the way we see the world.

Let’s talk about the Jamie Oliver episode from the most recent Legends series. What made this episode stand apart?

Adam: We knew this episode would be different because Jamie isn’t like the other chefs we have profiled before. In the past, we were often introducing someone’s story to the world for the first time. But this is Jamie Oliver. He is so well known globally. From the start, we knew we had to meet the moment. We switched to large format cameras and lenses to give it a different feel and a broader scope. We used the Leitz Elsies for the first time and found them to be gorgeous, cinematic, and elegant, a perfect match for the scale of Jamie’s fame.

Brian: We are using quite a bit of footage from Jamie’s twenty-five years on television. That amount of archival is new for us; we wanted to find an aesthetic that contrasted and elegantly integrated his TV career into our show’s world.

Adam: Much of Jamie’s early work was shot on 8mm and 16mm film, and I loved the juxtaposition with what we captured in large format digital.

That sense of cinematic identity seems important to the show overall. Do you consider outside cinematic references when preparing an episode?

Brian: There’s always a cinematic reference point. After we figured out the basics of how we could make the show, we wanted to widen our ambition by bringing in film references and rejecting more of the “rules” of how you’re supposed to shoot documentaries. We started having the same kinds of conversations you have on a narrative film in terms of locations, scheduling, and what each scene needs to yield.

Adam: A turning point for Brian and me was the season three episode we shot with Vladimir Mukhin, who runs a tasting menu restaurant in Moscow called White Rabbit. Fine dining in Russia has traditionally been international cuisine, but Vladimir set out to honor the country’s pre-Soviet culinary traditions. To tell that story, we came up with the idea of two visual narratives that intercut throughout the episode: one that takes place at his restaurant in Moscow, and one on a road trip where he explores his country’s food heritage. We shot the Moscow scenes on Leitz lenses, giving us clean, beautiful images, and then used vintage Super Baltars for the countryside/research material that gave us a soft and nostalgic quality. We’d never done anything like that on the show before, and it opened our eyes to how our gear choices could elevate our storytelling.

Brian: For the episode we did in Italy with pastry chef Corrado Assenza, we discussed Paolo Sorrentino’s Il Divo and La Grande Bellezza. We admired how his camera flowed so elegantly and wanted to try and translate that to documentary work, so we decided to shoot all our vérité on Steadicam. That created some production hiccups, and it was tough on our amazing Steadicam operator Joel Marsh, but to us, it felt like we’d unlocked another part of the show’s DNA. We’ve shot every one of our episodes in that style since.

What does the preparation for an episode look like?

Brian: I start by creating a grid and laying out the chef’s life linearly from beginning to present day. Then I go back through the biographical data and look for the important story beats. I’ll ask myself questions like, “If this is a traditional three-act hero’s journey, at what point is this character at their lowest? How are they going to overcome that? What are the takeaways for their entire life story?” Then Adam and I meet and start connecting story beats to visual scene ideas.

Adam: As Brian runs through the narrative and tells it to me like a story, we start tossing around ideas for more specific scene visuals, then hone in on the kinds of locations we want to find and scout, as well as any specialty gear we’ll need to bring ideas to life.

Brian: One of Adam’s many talents, in addition to his amazing technical and visual skills, is challenging every idea to make sure we’re pushing ourselves to do something fresh. He’s always asking if we’re copying ourselves. He’ll say, “How can we do something that we haven’t done before?” Or, “How can we go to the next level?”

Then, once we’ve gone through the full outline and connected visual scene ideas to the story beats, that outline becomes the blueprint for our producers Michael Hilliard and Drew Palombi to build a schedule.

Let’s talk about what makes a good episode. Each episode seems to have an arc to it. What structure are you working from?

Brian: My fellow EP Danny O’Malley is my brilliant partner on the story side. While the show quite strictly follows a traditional three-act structure, with a low point for our main character always coming towards the end of the second act, before redemption and ultimate success, we go much more granular than that with our structure work — all the way down to the scene level. In fact, we think about every scene in Chef’s Table as having three parts: exposition, action and reflection.

The exposition happens at the start of the scene, as the chef provides information that sets up the scene and establishes its goal. We usually cover this part of the scene in 24fps verité material. A good example of exposition might be that a young, aspiring chef has just gotten a shipment of fifty pounds more potatoes than he’d expected. He has to figure out what he’s going to do with them so they don’t go to waste. Then he sets his goal: he’s going to make the best french fries anyone’s ever made. That goal becomes the singular purpose of the scene, and when the chef states it, it cues the music.

At that point, the action part of the scene starts. Visually, we tend to cover this part of the scene in slow motion. We see the steps the chef takes to accomplish their goal. In my potato example, he’s chopping potatoes, blanching them, and frying them. In the middle there is normally an obstacle or two to overcome, a setback that forces the chef to solve a problem before reaching his or her goal.

Then the final part of the scene is the reflection. In this section, we try to provide a takeaway for the audience that changes their understanding of the chef and their journey. For my potato example, we might end up learning that making great french fries gave the chef confidence — from there, he started to believe the sky was the limit for his career. This reflection part of the scene tends to culminate with a shot of the finished dish from our food beauty shoot.

Adam: I don’t totally know what’s going on with this potato scene example, but suddenly I need French fries. Sticking with the analogy, I’m thinking like a cinematographer, and there are always choices we can make in the kitchen to support the story beats. If cutting and blanching the potatoes is the big turning point, maybe we turn off the fluorescents and pick a time when natural daylight is streaming in through the window. I try to find ways to subconsciously support the emotion and shape of each scene. Brian’s superpower is that he can identify and articulate these story arcs in such a way that allows us to make story-driven visual choices.

Brian: When you combine a bunch of scenes that work like we’ve described, with that combination of story beats and visual language, and you checkerboard them across our three-act structure, you’ve got yourself an episode!

Let’s talk about the food beauty shots. They’re always a high point of the show. What is your approach?

Brian: We call that section the “food symphony.” It’s the moment when the score swells, the dish title cards appear, and you see the finished plates in a beautiful montage. We’ll normally spend a day shooting the symphony in the restaurant; it’s the most intense shoot day on our schedule. Back when we started, these were shot from the point of view of the diner. That first Ben Shewry symphony was filmed on a white tablecloth, complete with place settings, with the camera dancing around the dish on a motion control rig, heightening the diner’s perspective.

Adam: Brian and I are always wary of repeating ourselves, and once the structure of the show had been established, we felt more comfortable being bolder and challenging ourselves. Lately, we’ve been designing symphonies that reflect the chef more than the diner’s experience — often evoking a feeling or a sense of place. We’ve shot symphonies of seafood dishes that appear to float on water in Spain, and others lit by crackling firelight in Sydney. It all depends on what sparks for us.

For Jamie Oliver, a prolific cookbook author, we created a book photoshoot set filled with tweezers, paintbrushes, and all sorts of food styling tools. We shot the symphony as a kind of “behind the scenes” of the book shoot, which gave it a subconscious connection to Jamie’s story. I rounded it out with bright white strobe lights to create a photo flash effect that also nods to Jamie’s tabloid level of celebrity.

How many cameras are you working with at a time?

Adam: We primarily shoot single-camera. We’ll use additional cameras during interviews to capture both a medium and a close-up, and during the food symphony for an overhead shot and a second macro angle. But the rest of the shoot, including the kitchen work and the vérité scenes on location, is all single-camera.

That approach really contributes to the filmic feel. As a team, you have to think carefully about the shot list and the pieces you need. If you do not get it just right, you cannot rely on a B-camera to save you. In a way, we are designing a workflow that forces the filmmaking to be precise and intentional.

Brian: That's the thing that the chefs really have to adjust to, especially if they've done television before, because they are used to having three cameras following them. They do it once and they're done. But we go, “no, no, no, we have to do this four or five times!” That can be frustrating for them, but it’s worth it for the control it gives us in image quality and editorial choice.

Adam: Once we get the scene dialed in on speed, we’ll go back through it in slow motion, then maybe again at a different frame rate, and then one more time with a diopter for macro inserts.

How does your creative collaboration continue into post?

Brian: Adam is always one of the first people to see a rough cut. Along with my fellow EPs, his feedback is always instrumental in the editing process. Then he really comes back into the process for color.

Adam: Shane Reed has colored every single episode of Chef’s Table and is crucial to shaping the look of the show, maintaining visual consistency over ten years. Chef’s Table was one of the first series on Netflix to finish in HDR, and Shane played a key role in developing the workflows and standards for the platform.

Creatively, he’s the best — a truly wonderful collaborator who always puts story first. I’m really proud of the look he’s established. It has a film emulation quality that gives each episode a cinematic treatment, but never to the point where the colors of the dishes feel manipulated. He preserves the integrity of the chef’s work. It is a fine line, and he walks it gracefully.

Chef’s Table is one of the earliest Netflix Originals and still going. What has that experience been like?

Brian: My fellow EP’s David, Andrew, Danny and I were texting earlier this year, and we all had to pinch ourselves when we realized this would be the tenth anniversary of the show. It can be difficult to reflect when you’re deep in the work, but we’re trying to remember how rare it is for a series to last a decade. I want to try and enjoy the ride as much as I can. It’s been one of the highlights of my career to work with Adam, continually refining and improving our work year after year.

After a decade, what keeps the team returning to Chef’s Table?

Adam: I think the nature of filmmaking, especially documentary filmmaking like Chef’s Table, is that because so much is out of your control, it’s impossible to make a perfect episode. So you keep coming back, in search of that unreachable goal. Refining your workflow, rethinking the structure. You can never be perfect, but the challenge keeps you going, pushing yourself and striving to get better. I’m proud of how far the show has evolved over the past decade. We have grown so much as filmmakers.

Brian: And of course, the lifestyle isn’t bad — eating at the world’s greatest restaurants with your friends.

Adam: It has been a great adventure, and I am excited to see where the next ten years take us.

The new season of Chef’s Table: Legends is available to stream now on Netflix.

Overview

DoP Adam Bricker

CHEF'S TABLE: LEGENDS

2025 | TV series

DoP Adam Bricker

Leitz lens ELSIE

Production Companies Boardwalk Pictures | Supper Club

Distribution Netflix

Country USA

Lens used

ELSIE

Character