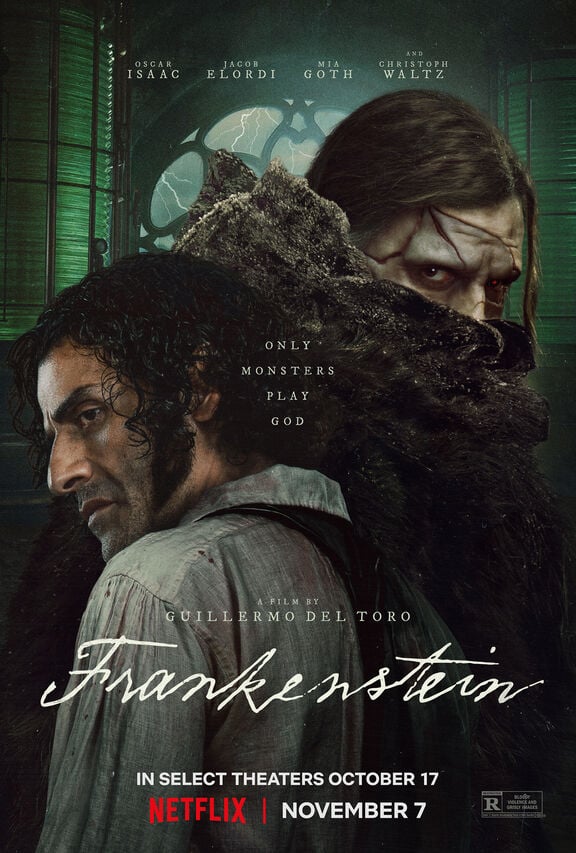

CINEMATOGRAPHER DAN LAUSTSEN, ASC, DFF KEEPS IT REAL ON FRANKENSTEIN

Frankenstein (2025)

Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein, photographed by Dan Laustsen, ASC, DFF, and produced by Netflix, reimagines Mary Shelley’s classic story as a rich, poignant drama that navigates the themes of creation, loss, and forgiveness. The film centers on a driven scientist (Oscar Issac) whose experiment gives rise to a creature that is monstrous and yet deeply human, creating a complicated bond between father and son that plays out with a balance of big, striking visuals and grounded emotional moments.

Seth Emmons: You’ve had a history of successful collaborations with director Guillermo del Toro. What did you think when you saw the script for Frankenstein and his angle of a father/son drama?

Dan Laustsen, ASC, DFF: I’ve done five movies with him now, so we know each other pretty well, going many, many years back. Even when we did Mimic almost 30 years ago, we were talking about our dream projects, and he said his dream project would be Frankenstein. I didn’t pay much attention to it, because of course he likes these kinds of creatures and monsters. But when we did Nightmare Alley, he said, “I’m pretty sure our next project is going to be Frankenstein.”

So I read the book, and I loved it. The book is amazing. But then I got the screenplay, and of course he’s changed everything, like Guillermo does. It’s not a horror movie at all. It’s 100 percent a drama. And it’s a love story—a very strong love story. It’s a film about a father and son and forgiveness. It was super interesting for me. It was like, “Wow, this is new!” For me, both as a filmmaker and as a daddy, it was super interesting. I think love and forgiveness are very important things in our lives, and it’s always nice to work on something that you feel emotionally attached to. But that is the Guillermo del Toro way to do things. It’s amazing.

What were some of your visual language and aesthetic ideas going into this film?

The story is a classic story, and we wanted to make a classic movie, but we didn’t want it to look like an old-fashioned movie, so we talked a lot about what we wanted to do. Of course, a lot of the choices come from Guillermo. He’s the director, and he knows exactly how he wants to tell the story and how he’s going to edit it together, and I think that’s the way it should be. The director is telling his story, and we are going to help him do that. I can have all kinds of ideas about how to tell the story visually, but if he doesn’t agree, then it’s an issue. But because we know each other so well, we have exactly the same feelings about a lot of things.

We wanted to shoot it as a modern-looking movie, which meant shooting with much wider angles, moving the camera, and doing longer takes than what we have done before. We are much more wide-angle on this movie than before, and the way we got there was by shooting large format.

We shot a little bit of large format with the ARRI Alexa 65 on Nightmare Alley, but this would be a whole movie with a lot of camera movement. When we started prep, I spoke to my Steadicam operator, James Frater, about it. The camera is a heavy beast, but he said we could do it. So we shot the whole movie with the 65. To be wide, everything is shot on the Leitz THALIA 65 lenses, with our main lens being the 24mm for about 90 percent of the movie, which is a pretty wide lens in large format but doesn’t have distortion.

Was the wide angle of view the primary motivation to go with large format?

Large format is just a very nice format. It’s a little bit like the old 70mm film. The details in the face, the skin tones, and the lack of depth of field are so beautiful. I just think it’s a beautiful way to treat the sets, the storytelling, and the actors at the same time.

We often started in a big wide shot, seeing the room, the sets, their world, and then we would move the camera into a close-up in the same take. It’s very dramatic and very cool to play the story that way. There’s a lot of technical challenge in doing that because you have to light the whole set, but when you come into a nice, clean shot at the end, it’s really beautiful and very strong for the story. You can’t go in and make a nice close-up of one of the actors if it’s distorting too much, which is why we needed the large format and the THALIA 65 lenses.

Guillermo also likes to do as much as possible in camera and for real on set. We want to see the sets that production designer Tamara Deverell made. We want to see the beautiful costumes that costume designer Kate Hawley made. We want to see creature designer Mike Hill’s work with the Creature. With the large format, we can capture so much detail, but we don’t have to have a flat image. Large format helps that because the depth of field is so shallow. Of course, that’s a big issue for Steadicam and for my 1st AC, Doug Lavender, because the camera is moving all the time. But they’re the best, and they made it work.

There are two challenges in shooting large format: the T-stop and the sharpness. I shot the same T-stop for the whole film. The 24mm THALIA 65 is only T3.6, and I closed down a bit to T4. Of course, you need some light for that, especially when you have huge sets. The way I’m lighting is to have all the lights outside the sets. We never had lights inside, so the set is kind of our gobo. Whether we’re shooting on location or in a studio, all the lights are outside. I used all tungsten: 20Ks, Dinos, Raptors. It’s a little bit old fashioned.

With the large format and the lenses, sometimes it’s getting too sharp, so I always shoot with a Tiffen Black Pro-Mist filter inside the camera. It’s a click-on magnetic filter that attaches to the back of the lens. It makes the highlights burn out a little bit less, and that’s very nice for skin tones and candles. We had a lot of candles and torches on Frankenstein, and you see that they’re glowing a little bit around the highlights. But because the filter is behind the lens, you keep a richness in the blacks, and if you get a flare, it’s a lens flare and not a filter flare.

With the importance of the world around the action, would you have shot at a shallower depth of field if you had the chance?

No, I would not, because I like T4. I don’t like doing a close-up with only one eye sharp. I like having some depth of field. I’m only ever shooting wide open if I have an issue with the background. It’s always nice to have a little bit of flexibility for exposure issues, but these THALIA 65 lenses are performing so nicely. I like them very much.

I read in one interview where you said that you and del Toro “like to stay on the dark side of the light.” Can you say more about how you work with light on set?

We always have a discussion about the blacks. We like the blacks to be pitch black, but Guillermo likes to have the blacks blacker than I do—and I like black—so he’s just teasing me all the time. The look we got on Frankenstein is the look we wanted to have. If you see our dailies from the DIT and the final movie, the color palette is exactly the same. Of course, we are changing power windows and maybe we crush the blacks a little bit more, but not much.

The color palette of everything is so precise—the costumes, the makeup, the creature design, the lighting. We tested the colors so much before shooting that we didn’t change the color palette at all during production. If we were to try to move the color more toward orange or blue, everything is—it’s not that it falls apart—but it becomes another look.

A lot of lighting these days is LED, and you can dial in the colors, but for Frankenstein we used tungsten and put gels on them to change the color. We used Steel Blue a lot. The Steel Blue gel on a tungsten light is very beautiful, so that was our key light.

Was this the first film that you have done with an HDR finish?

No, we did it on John Wick: Chapter 4. I think actually The Gorge was as well. The Gorge was also shot on 65 with Leitz lenses, but that was not a theatrical release.

HDR is amazing—it’s really beautiful—but we don’t have an HDR monitor on set. I think HDR is a plus. I shoot as well as I can, and when we go into HDR, we get just a little bit more detail, but we might still crush the blacks. For us, black is very important, because we always like to stay on the dark side of the light.

Del Toro usually doesn’t storyboard his shots, but he likes to shoot chronologically. How does that play out on set?

The only storyboards I remember are what we did for the fight on the ship with the Creature, just for the action sequences. But the storyboard is very, very brief. It’s so everybody knows approximately what we are going to be looking at—what’s the angle, things like that. But when you start to shoot that sequence, the storyboard is just gone.

Guillermo makes his notebooks all the time, which are small sketches for him, but that’s not for everybody. He might show me and maybe a few other people. But of course, that sketch is changing all day long. Guillermo and I are big fans of very specific preparation, but if something better comes up on the day, we are going to do that. We change. If we see something better, if the actors come with something, or Guillermo feels there is a better way to do it, we just do that. We are very open and very flexible, and that’s the reason the set is lit 360 degrees.

When you see the way the camera moves, all that is designed so precisely because he always knows where he’s coming from and where he’s going. While we are setting the next shot up, he’s editing what we have done before. The camera is working or moving all the time, and the close-up is not just a close-up. The close-up is part of a moving camera, because we are turning around all the time. We are shooting the story. We are following the actors. So we are starting at the beginning, and then we are shooting through the scene.

What are the challenges of shooting chronologically? What are the benefits?

It’s so complicated and really difficult. We started to do it a little bit on Crimson Peak. I don’t remember if we did it on Mimic. But on The Shape of Water we did it all the time, and you can see the way all the shots are blending perfectly into each other. That’s because Guillermo was designing it and knew where he was coming in and out every time.

It’s fantastic for the director. It’s amazing for the actors, of course, because they’re in the story. I think more and more directors like to do that, because then they know where they are story-wise.

As a cinematographer, it’s time-consuming. Lighting-wise, it’s a challenge, and you really have to be on your toes so you’re not changing the light too much. Everything we’re doing with Guillermo is with one camera. There’s no B camera, so the camera is moving quite a lot from one shot to the next. I’m sure some people would not be happy about it, because it’s much faster to shoot with blocking, but I think it’s worth it, because it’s really great for the story, the director, and the actors. We’re not shooting a schedule; we’re trying to shoot a movie.

What I really love about moviemaking is teamwork—the director, myself, the whole crew. It’s a really big pleasure for me to work together with everybody on the set. We are working for Guillermo, we are working for Chad [Stahelski], we are working for whoever we are working for, and for the movie itself. I think that teamwork is amazing. Everybody is carrying that movie on their backs, and everybody is so invested. Very few people on the film set are coming to work just thinking, “Oh, what else should I do?” They’re coming to work because they love the process. They love to make movies. I really love it.

Are there any other examples in the film where you prioritized shooting something real in camera?

Guillermo and I like to shoot as much as we can for real. That’s the reason he decided to build the ship on a gimbal in a parking lot in Toronto. That was a big deal. Tamara and her team did a really fantastic job.

Also, all the inside shots when the lab is exploding—that’s a miniature we shot in London. We shot the collapse of the castle, the explosions and the collapse inside, all of that in miniature. It’s the only thing we didn’t shoot with Alexa and Leitz. We used the ARRI Signature Primes with a diffusion filter behind the lens and a RED camera, because Dennis Berardi, the visual effects supervisor, wanted to go high speed but still at 6.5K.

Guillermo and I flew over to London because we had a gap between the shooting in Toronto and the shooting in Scotland. We went over there for two to three weeks to shoot that miniature. I have never done such big miniatures before, but that was amazing. Those guys built amazing, beautiful miniatures. It worked extremely well. That team in London was so sharp, and they did a perfect job. We were just there to supervise and make sure the light was going to be the same.

We shot T11 at 96 fps, so we needed a lot more light. The miniature was pretty big—1:20. So again, all lights outside. I brought the same DIT to do that as well, and we had all the references for the set because we shot the A side first and knew exactly how it looked on the big set. I think if we had shot the B side first, that could have been a problem.

We did have a few color issues. We couldn’t get enough exposure out of the tungsten lights, so we used HMIs and had to color them with gels. That was not a big deal, but that was the biggest change. A lot of things were lit with fire. When you see the scene, there are real flame bars and things like that, so we wanted to have the same color balance. But it wasn’t a big deal. We had our reference, and we knew what we liked and didn’t like. I think as long as you have the same taste, it’s not a big deal to change from one thing to another, because you still look at it the same way. Guillermo and I are really good at doing that together. It’s just like working together with your best friend. It’s really cool.

Was the choice to do miniatures as opposed to a more VFX-heavy version because of Guillermo’s preference for capturing things in camera?

Dan Laustsen: One hundred percent. That was his decision. Of course, we talked about it, and we both wanted to do it as a miniature. And I don’t think it was more expensive, because visual effects are not cheap. But this way you see real things falling down. Of course, visual effects are still helping a lot with cleanup. Without visual effects, I think all movies would have a problem now, because we are so used to set extensions and things like that. But again, I really believe it’s cheaper to build it realistically.

You have a great eye for photography. Could you speak to your history with photography and how it relates to your cinematography? Do they inform each other, or are they two separate worlds for you?

No, no—I only have one brain, and two eyes, of course. But I’m not coming from a family with any arts. My mom was a schoolteacher, and my dad was a factory worker. But when I was about 16, my buddy and I decided to try to take some pictures, so we bought a camera. We worked as dishwashers on a boat over the summer vacation, and we started to take pictures. My daddy made a darkroom in the basement, and that was the start. In those days, there was no YouTube—there was nothing—so we made all the mistakes in the world.

I’m educated as a fashion and commercial photographer. And actually, the large format comes from there, because when I was starting out, we were shooting a lot of things with 8x10. And that’s a beautiful, beautiful format. I went to film school after becoming a professional photographer.

It was funny—when I went to film school, it all seemed so complex to me that I stopped taking pictures. It was too much for me. For many years, I just took pictures of my kids and on vacations and all that, but photography just seemed to disappear. I don’t know why.

Then I bought a Leica S medium-format camera many years ago. That was the first time I started to work with Leica lenses. And those same S lenses are the basis for the Leitz THALIA 65 lenses. I think stills were bringing me into THALIA 65, because I liked the S lenses so much—and I still have them.

I just love to take stills. I think it’s fantastic, and it’s fun, and it’s given me a lot of happiness. It’s the same feeling as making art you like. There are some people who don’t take stills as cinematographers, and people can do whatever, but for me, I really believe that if you’re doing something all the time, you’re getting better.

If you listen to some of the big old masters—Richard Avedon and Irving Penn and those guys—they were working that way all the time. It’s the same with tennis players: if you’re a good tennis player, you have to train every day. For me, I just love it. I like to take a camera out and take pictures.

I was very much into landscapes for many years, but now I’m going a little bit more into people. I like to take pictures of old people—the people who have some wisdom in their eyes. I wish I could shoot 8x10, but I can’t do that, so I have to use the Leica S. The details, all the textures—I think it’s so beautiful, and I have a lot of fun doing it. Sometimes I’m running out of time because the movies we’re doing right now are crazy, but I love it. It’s so cool. And yeah—I love it!

Frankenstein is streaming now on Netflix

Overview

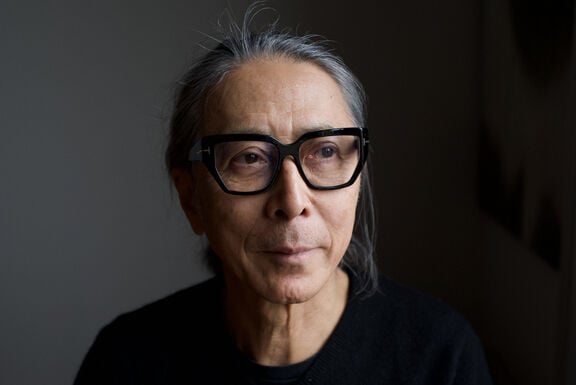

DoP Dan Laustsen

Frankenstein

2025 | movie

DoP Dan Laustsen, ASC, DFF

Director Guillermo del Toro

Leitz lens THALIA 65

Camera ARRI Alexa 65

Production Companies Bluegrass Films | Double Dare You (DDY)

Distribution Netflix

Equipment Supplier ARRI Rental | Los Angeles

Country USA

Lens used

THALIA 65

Legacy

Crafted to shape great stories. One set of simply exceptional lenses for unlimited scope.