SEARCHING FOR THE “ALWAYS ANSWER” WITH BEN RICHARDSON, ASC AND LEITZ SUMMILUX-C LENSES

1923 (2022-2025)

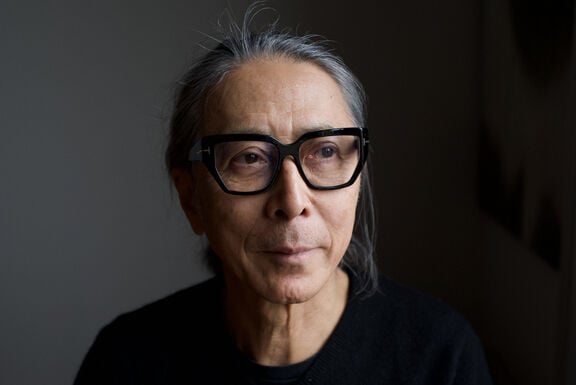

Cinematographer Ben Richardson, ASC has been nominated for multiple Emmy awards and American Society of Cinematographer awards, and has received many accolades for his first feature film Beasts of the Southern Wild. In recent years Ben has collaborated closely with Taylor Sheridan, shooting and directing much of Taylor’s TV shows and films to great critical acclaim.

Seth Emmons: You’ve worked with writer and director Taylor Sheridan on a prolific number of projects thus far. Can you speak to the visual language that the two of you have created together? How does it intersect with your personal aesthetic?

Ben Richardson, ASC: The scope of Taylor’s work now is pretty vast and there are multiple shows in a production at once. While there isn’t a desire for a unified style in any way, there is a desire for quality, for an aesthetic that works, and that Taylor finds appealing. We found the seed of that aesthetic when I shot the film Wind River, which he wrote and directed, and have continued to refine it since then.

After that I shot the first season of Yellowstone, his feature Those Who Wish Me Dead, the pilot for Mayor of Kingstown, and significant blocks of both 1883 and 1923, all Taylor projects. Over the years I’ve inevitably had to hand off some of the photography to other cinematographers and have come to realize just how difficult it is to encapsulate the visual language in terms of rules.

One thing Taylor and I both love is the long lens cinematic feel. We love to compress the background, bring it closer to the characters. To me it's one of the more cinematic looks because it is a little out of our usual experience of the world. When you put an 85 mm or 100 mm lens on a Super 35 frame and make that your wide shot for a Montana landscape the mountains become huge and present, the trees and woods feel vast and imposing. The landscapes seem to go on forever.

Similarly, with close-ups on Yellowstone, we might shoot a forehead-to-chin shot on a 135 mm or 180 mm, or even out at the end of a long zoom, around 300-400 mm. I think there is something very intimate about a long lens close-up, without the aggressive sense of proximity that a wider lensed close-up can create. I think that’s the reason Hollywood has loved them for so many years.

As a general rule, I don't love a wide lens up close. For example, the way Terry Gilliam might throw on an 18mm or 21mm lens and just stuff it up in Brad Pitt's face. It creates a sort of caricatured, cartoonish representation of the person’s head. To me that perspective looks kind of crazy.

I think there's a reason the long lens look has been a staple of cinema for so many decades. It does something special to the image. The compression and the fact that all the elements get sort of stacked can be very dynamic and creates a break from reality. When you see two people walking and they're filling two-thirds the height of the frame, but you're shooting that on a 135 mm or a 180 mm or even a 400 mm, that is not a natural perspective; it works to elevate and heighten moments.

So yeah, the wider closer style has just never been super appealing to me. And it isn’t part of Taylor’s general aesthetic either. I do have a bit of a beef with the current TV style of very wide lensing, deep composition, and quite stylized lighting. I don't want to name check shows because a lot of them are very successful and in many ways very beautiful, but I find it quite distancing in the sense that you can pause on a frame and go, "Wow, what a beautiful image that is."

To me that isn't the purpose of the cinematic use of the camera. I don't want people to stop and admire an individual frame. I want them to be immersed in an experience built from the pieces that we are choosing to show them. They can go back later and admire some of the art or the aesthetic choices, but in the first viewing I want people immersed in that experience and I don't want to do anything with the camera that would break that unless it's for a very good reason, you know?

That said, I am in awe of people like Roger Deakins, and very few others, who can shoot almost an entire film on a handful of lenses with the 35 mm as the long lens and the 27 mm as the wide. After Those Who Wish Me Dead, I shot the HBO series Mare of Easttown, which was written by Brad Ingelsby and directed by Craig Zobel, and had to explore and play with composition using wider focal lengths in a way that I hadn't on Taylor’s projects at all.

What made Mare of Easttown different?

Mare is a more intimate story, and the setting played a big role as well. I knew that part of the visual language would be more about the landscape of the characters’ faces than about the physical landscape as in Montana. I had to move my visual thinking from the Great Room in the Dutton lodge to Mare’s modest kitchen and dining room. The spaces were smaller and a lot of the techniques I’d developed and honed with Taylor, and gotten quite comfortable with, were not going to work at all. I had to explore wider lensing, or we simply wouldn’t get any interesting frames.

The lens tests for Mare might have been the most comprehensive test I’ve ever done. I shot test footage with a large number of different manufacturers’ lenses, took the footage home, and watched it over and over and over. I went way down the rabbit hole. There are a lot of good lenses out there, but there was just something about the Leitz SUMMILUX-C lenses that felt like coming home. Something about them tickled the part of my brain that was looking for certain things that I hadn’t yet seen in modern lenses, but loved in older, more vintage lens designs.

I know we would need to get close to many of the characters in Mare and in testing we found that somewhere in the 50 mm to 65 mm range with the Summiluxes was kind of a magical place for doing closeups that felt incredibly intimate. We actually had to be careful with it, to not always go to that look and frame. The performances were so strong throughout, it was almost too much, and we wanted to save it for the biggest moments.

But there was just something about those lenses… They really checked all my boxes, they had the sharpness where I wanted it, they had the fall off the way I wanted it, and just beautiful defocus characteristics. Now I come back to them over and over again.

SE: Stepping from there forward to 1883 and 1923, did you move back to the long lens aesthetic?

Yes, mostly. I was very pleased with all the choices we made on Mare, and I think the result for the storytelling was perfect. But, after a hundred plus days shooting in this very different style, when I came back for 1883 I felt that I had a larger creative palette available to me in a way that I really enjoyed. And I brought the SUMMILUX-C lenses with me as well. Both 1883 and 1923 include more wider, closer shots than I think Yellowstone ever had, but approached very carefully and delicately. Although, in my world those wider shots mean using a 50 mm or 65 mm as opposed to our typical 135 mm. Once I learned a level of comfort with those new options then we weren’t always stuck, saying, "Well, let’s go for the 135 or the 180 for the close."

And I do understand it, there's something to be said for having the physical proximity of the lens within a few feet of the actors instead of, you know, 10 or 12 feet back. The audience doesn’t consciously know that they're physically closer, but if it's an intensely beautiful moment or scary moment, that proximity can allow an audience to experience differently what's being given off by the performers.

But then with wider shots, if you do get to the place where you are choosing a wider lens to simply fit some of the set or location in, you must be sensitive to what that lens might be doing or saying. The trade-off might be that suddenly if a character needs to walk halfway across the room they’ll grow five times in size, and now you’re saying something to the audience that you may not have intended. It’s very delicate and I am very judicious in my camera position and height. You have to balance those things out so you can get more of a complete frame of a space without any of those issues that wide lenses usually trigger for me.

SE: What has your progression of lens choices over time looked like?

I shot several of my early projects on the old Zeiss Standard Speed lenses, the T2.1. I still own a set. There is something special about them. I think people forget how these little hunks of Zeiss glass were remarkable designs for their time. They are beautifully sharp in the areas you care about, and the fall off is natural and gradual with some interesting textures in the defocused background.

But Wind River was one of the last projects I shot on the Zeiss Standards. When we started season one of Yellowstone I decided I just couldn’t in good conscience put another assistant through trying to work with them. They’re just not built for modern use with multiple lens motors. They tend to bind and have other physical challenges. And they’re terribly matched. While they have their strengths and I do love them, I just couldn’t shoot another big project with them.

I needed to find a more modern lens and tested 10 or 11 lens sets, which at the time was pretty extensive. I had shot with the Leitz SUMMILUX-C lenses on a couple of commercials and was already quite taken with the characteristics that I mentioned before. The only issue being that at launch they were kind of a rare thing and quite expensive to rent. Of the more available sets, the Arri/Zeiss Ultra Primes felt like the best lineage at the time even though they had their flaws. They have some of that Zeiss Standard sort of quality to the image. I’m not a wide-aperture chaser and don’t need a T1.3 or T1.4 for technical reasons. I’m perfectly happy with a T2.0 lens. So, I used the Ultra Primes on Yellowstone season one.

SE: What are you looking for when you’re testing lenses?

Out-of-focus characteristics are very important to me. It can be challenging to define what you like or don’t about defocused background, but it is arguably one of the most important things in lens design. Ultimately that is going to end up being 50% of your screen image most of the time. I do want some of those characteristics that optical designers would probably call aberrations. When there are blur circles that are slightly glowing over the foreground subject, or slight onion ring edges on the defocused background elements, those are informing the audience of detail that exists in that background and to me that it is an important part of the scene that I don’t like being flawlessly blurred away.

One thing I noticed when testing for Mare was that the more modern, optically “perfect” lenses I tested felt like a scientific rendering of a scene, which to me was as distancing as using too much diffusion. “Organic” is a word that gets thrown around a lot, but I have a sense of what it means to me, and that’s how I define the look of the Leitz SUMMILUX-C lenses. It’s about having sharpness where you want it, the ability to control that sharpness through aperture use, and how much depth you want for each shot or moment.

And when things do fall off, I don’t want them to fall off into a perfect blur. There are some lenses I’ve used that felt like the background had been put through a Photoshop Gaussian blur. It’s a very mathematically exact kind of defocus, but it almost feels wrong when you see it on the screen. It’s artificial and everything is just evenly smoothed away. I’ve had people ask me if certain shots are on blue screen because the foreground subject is tack sharp to the point of clinical perfection and the background has blurred out too neatly. It just doesn’t feel real. I want the integration of the background and the subject that the SUMMILUX-C lenses offer.

I believe our experience of the world is intrinsically cinematic. We have films of junk across our eyes, we have little floaters, we have wetness in our eyes. There is flare, haze, stuff is happening. If you stop and think about it, when you’re driving at night and see headlights, they aren’t rendered as the pure, scientifically objective version of themselves. That would mean seeing the illuminated area of the headlight as bright, but once you get to the non-illuminated part of the car it goes to pure black. That’s not the way we see the world. There are interplays of light and reflections and flares within our eyes. Our brain filters them, so we think we’re seeing the world, “as it is,” but they’re there and I think we’re subtly aware of them. I think it’s really important to have a lensing approach that gently captures some of those characteristics. I want to create an impression of the world as it seems to us.

I genuinely do admire and respect those people who select a different lens set for different projects based on different reasons, but that’s never been my MO. If I want to change the image I’ll do it with lighting, with focal length selection choices. With the Leitz SUMMILUX-C I couldn’t be happier. They’re perfectly matched for look, and it’s a look I happen to love. Compared to a lot of lenses, they’re compact and relatively lightweight; and they have high-quality housings and consistent focus/aperture rings, which makes them great on a fast-moving set. It’s one of the elements that I feel is now solved for my work, certainly for the foreseeable future. It just feels like something that I no longer have to think about, which is a very nice feeling.

We mentioned Deakins earlier who is famous for using the same camera and lens pairing across multiple films and still creating unique looks through lighting, set design, etc. Do you approach filmmaking in a similar way?

I try to approach everything in that way. I’m constantly looking for the “always answer,” the thing that is going to work best for me in almost every situation. For me there is an ideal answer out there to almost every question, every choice: my camera, equipment bag, the jacket I’m wearing on set, lenses, LUTS, you name it. There is something out there that is the best for me personally. And when I find that thing, solve that problem, and check it off the list…oh my God, I am so happy.

I feel that over the course of my life I am iterating towards my optimized creative existence, toward having all the things in place to reduce the number of decisions each day to a minimum. That leaves more room for the creative part of the process, which is the use of those tools. I truly enjoy the process of finding out how and why different technologies benefit us in the creation of this art and refining those choices as I go along. For example, I only use one LUT when shooting. It was originally derived from a film emulation based on scans of film stock and we’ve tweaked and refined it over the years. The original was arguably a little too slavish to the film look. It had those cyan-blacks that a film print has, but it was a little distracting when everything was a little bluish and cool in the corners. But now we’ve refined that look to the point where I don’t even think about it. It’s just the starting point for the work on set, and the work in the grade.

In the same way, I’ve used the ARRI Alexa Mini for many years now. I started shooting with the original Alexa when it was released, and although I test other cameras periodically, to me the characteristics and practical aspects of the camera suit me best. I believe we did some of season one of Yellowstone on the Amira because of the form factor, but quickly switched to the Mini when it came out. And now we’re on the Alexa 35 for 1923. For all the contemporary love for larger sensor formats, to me there is something slightly magical about the Super 35 size. Besides the core technical reasons, it’s got a very deep history in cinema, and it allows you to pull in extra bits of equipment from time to time like specialty lenses.

Have you shot any of your projects in large format?

In all my testing and understanding of the physical and optical principles involved, I've never felt the desire to go to a larger format for motion. Not least because when you go to a larger format people are always about depth of field with the implication being that large format offers an automatically shallower depth of field, and by God can we stop chasing the shallowest depth of field, please! But that’s only the case if you’ve got lenses with a correspondingly wide aperture, which wasn’t initially the case. Until very recently a good T1.4 Super 35 lens beat most of the available larger format covering lenses if you were primarily concerned with depth-of-field. Resolution is another factor, but again, I’ve not personally seen a final deliverable image that I felt would have benefitted from the extra pixel resolution.

But now the introduction of the [ARRI] Alexa 35 is what I’ve been waiting for. For me, there is now the definitive Super 35 digital sensor and I’m never going to have to have the stupid 4K debate again. ARRI has always been clear it’s the quality of the pixels they care about, not the quantity, and I'm an absolute subscriber to that principle. If you are capturing rich, deep color information and dynamic range, if you are truly extracting the maximum acutance possible in terms of pixel sharpness, then you can work with those images to the point where you are literally seeing pixels before it becomes artificial looking. It’s such a good organic image. But now that the Alexa 35 exists, my God, that’s the one.

Do you shoot full Open Gate?

I have a defined crop, slightly smaller than the open gate, but we shoot the whole sensor, including the “look around” area, which isn’t a new idea of course. But my preferred crop is quite specific. An actual piece of Super 35mm film is 24.89 mm wide whereas the Alexa Mini sensor is 28.25 mm and the Alexa 35 is 27.99 mm. I’ve settled on 24 mm as my standard sensor width for shooting, and I adjust the crop on each camera to give me that 24 mm as the final deliverable area. It means that my lenses behave predictably across different cameras, and I don’t need all that extra resolution in the final image even on the Mini.

On the Mini that crop means we’re down to about 2800 pixel across, but we’ve aired closeups that we punched in another 20% or 25%. So, you’re down to what? 2200 pixels across the width of the image. For the first two seasons of Yellowstone and on Mare of Easttown we framed for that crop but shot the full sensor in ProRes 4444 and the images look stunning.

I’m a big fan of the 2:1 aspect ratio for these large-scale shows. It’s got a lot of the 2.39:1 feel but makes better use of people’s TVs. All the monitors on set have the frame lines so we’re composing for that 24mm sensor width, but we’ll have that extra area in post for stabilization or the occasional reframe or adjustment. There’s often the need to fix a horizon in post, or sometimes you just feel the shot needs a bit of rotation aesthetically. Maybe the camera wasn’t leveled on set, or it just feels weird for whatever reason. If we shot all the way to the edges we’d have nowhere to go and would have to start cropping to rotate and now the intended frame is changing.

With the look around you have that flexibility on all four sides, and it’s saved us so many times. These shows are shot so fast, and we do relatively few takes, sometimes one or two takes on big complex action moments and things like that. The ability to subtly massage shots after the fact without compromising what you were going for on the day is a big deal.

But the tools we have now mean I’m never worried about the quality of the image. With such good lenses I don't think much about the resolution part of it because I know that the lens is likely out-resolving the sensor anyway. Blowing up images does mean that your lenses must be clean and sharp. When it comes to that, I’ve found my answer with the Leitz SUMMILUX-C primes. When I switched to them and started seeing the dailies come in, I said to myself, "There you go. That's the answer. Don't need to think about that one ever again.”

Overview

DoP Ben Richardson

1923

2022-2025 | series

DoP Ben Richardson, ASC | Corrin Hodgson | Robert McLachlan

Director Ben Richardson | Guy Ferland

Leitz lens SUMMILUX-C

Production Companies 101 Studios | Bosque Ranch Productions | MTV Entertainment Studios

Distribution Paramount+ | SkyShowtime

Awards 4 wins & 22 nominations total

Equipment Supplier Keslow Camera | Los Angeles

Country USA

Lens used

SUMMILUX-C

Performance

Fast, compact, reliable, beautiful in color and excellent in contrast.