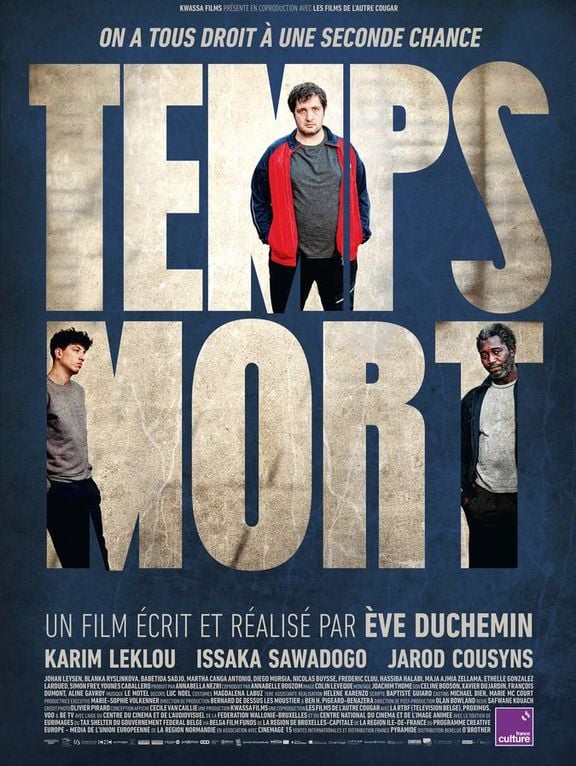

Gran Turismo

2023 | movie

DoP Jacques Jouffret

Director Neill Blomkamp

Leitz lens M 0.8

Camera SONY Venice 2, Rialto

Production Companies 2.0 Entertainment | Michael De Luca Productions | PlayStation Productions | Sony Pictures Entertainment (SPE) | Trigger Street Productions I TSG Enternainment I Marzano Films

Distribution Columbia Pictures | Sony Pictures Releasing International | Universal Pictures International (UPI) I HKC Entertainment I Feelgood Entertainment I Big Picture 2 Films I B&H Film Distribution I TME Films I United International Pictures I Plaion Pictures

Awards 3 nominations

Equipment Supplier Panavision | London

Country USA

GRAN TURISMO: JACQUES JOUFFRET, ASC PUTS LEITZ M 0.8 IN THE FAST LANE

Cinematographer Jacques Jouffret, ASC joins director Neill Blomkamp in bringing the incredible true story of video game player turned race car driver Jann Mardenborough to the screen in Gran Turismo. Together an unlikely cast of characters will change the sport of racing forever.

Seth Emmons: Based on the title one could assume this is a film about the creation of a video game, but it’s not.

Jacques Jouffret, ASC: Not at all, although there is a connection to the video game. It is actually a coming of age true story. The main character, a young man called Jann, starts playing the Playstation car racing game Gran Turismo in his bedroom and becomes so good at it that he gets to go to the Nissan GT Academy, a competition to turn video game players into race car drivers, and earns the top spot. With that comes a contract and the opportunity to race real cars in competition, including at Le Mans.

How did you get attached to this project?

I met director Neill Blomkamp when I interviewed with him for a different project. For some reason that project was pushed, but Neill and I got along very well and a month or two later he called me and said, “I’ve got this new project. Let’s do it together.”

What were some of the early themes or big picture ideas you and Neill discussed at the beginning of this film?

From the beginning the most important thing for Neill was to have a documentary feel because it is a true story. We talked about past racing films like Le Mans with Steve McQueen and Days of Thunder, but this was a very different type of animal. Neill always wanted to shoot it in a very real and simplistic way. We would shoot at the actual locations and race tracks where these races took place and not use any artifice or visual effects, all real speed on a real track in a straightforward fashion. Two of the main things we considered with framing and camera mounting was conveying the speed and violence of these cars.

How do you mean?

These cars are extremely fast. When they are at full speed doing 200 miles an hour it’s super hot inside the car and they’re bouncing and jerking all over. Nothing is smooth or easy so we wanted to show that. It’s challenging to do, but one way we did it was by keeping all of the exteriors shot from the camera car low to the ground, just a few inches off the tarmac. With framing we included very little sky because it doesn’t give a sense of speed. Instead, we focused on the tarmac, the wheels, lots of debris, all things that help the viewer feel the speed.

We didn’t stabilize the car mounted shots and also removed all the stabilization from the remote head on the camera car. Most people don’t see just how violent the sport is. We wanted that to be visceral for the audience. These cars vibrate like hell and if we stabilized the shots you would lose that very important element of the race.

What were your camera and lens setups like?

During the racing scenes we used 6-7 Sony Venice cameras, 3-4 RED Komodos, and 3-4 RED V-Raptor cameras, all in various positions and configurations.

We used real race cars so space inside was very limited. Our main cockpit setup was three Sony Venice cameras with bodies mounted in the back of the car and the Rialto extensions using Leitz M 0.8 lenses inside the cockpit: one in the center, one to the left, and one to the right. For editing, this allowed us to cut back into the cockpit on the correct side depending on where the previous shot from outside the car was coming from. On the outside of the car we hard mounted cameras to get that feel of the road and the wheels, as well as a camera facing forward to capture cars passing in front and one pointing behind the car.

For a camera vehicle we ended up rigging up an actual GT3 car that we found in the UK. It was the only way to keep up with the real cars going 200 miles per hour. We had a great driver who was somehow able to keep up even with a whole bunch of cameras on his car. It was a lot of extra weight.

We also had to modify the race cars that Archie Madekwe who played Jann would be inside. We were running three different types of cars: GT-R, GT3, and eventually the LMP2 car at Le Mans. We added pods on top of each one so that a real race car driver would be driving from on top of the car with Archie in the cockpit.

We had three drone teams: two using FPV drones flying Komodos with Leitz M 0.8 lenses and a heavy lifting cinematic drone with a V-Raptor and M 0.8 lenses. They were spread out at various sections of the tracks to pick up action. We also had cameras with long lenses in different places.

We shot everything full sensor with a 2.40:1 extraction. The Komodo was Super 35 but the Venice 2 and V-Raptor were shooting 8K. Putting everything together worked really well. There weren’t any problems matching camera formats.

Did the game itself influence any of the creative choices?

Part of the visual language that Neill wanted to use was a connection to the game itself. For players of the PlayStation game there are some iconic camera angles. Looking out through the windshield from inside the cockpit and seeing the steering wheel and hands is a classic image from the game so we recreated that with a helmet-mounted camera and the M 0.8 lenses.

Another of the most well-known angles is the overhead shot from behind looking down at the car. From that perspective you see everything that’s happening in front of you on the track. To achieve this we hard-mounted a plate on the bottom of the car connected to a truss coming up behind the car with the camera mounted at the top of the truss pointing somewhat downward. For this we needed a somewhat wider lens and used a Panavision Panaspeed lens.

How did you end up making your lens choices?

I had decided I wanted to use the Panaspeed lenses for the dramatic scenes, but I was having a problem with the cramped cockpits of the cars. In my talks with Panavision UK I said, “I need you to give me a very, very compact lens.” And they told me, “Why don’t you try the Leitz M 0.8 lenses.” My first thought was, “Bingo!” It was that kind of moment. The form factor is perfect. They’re f/1.4, full frame, and the Leitz M adapter for the Rialto is extremely small.

As for the character of the lenses, they have this portrait feel with great depth and a center weighted image. Inside the cockpit I was just interested in the driver so it was a perfect match. I used some diopters screwed into the front of the lens to bring the minimum focus to where I needed it to be, which I loved even more because it gave me a little bit more depth, a little bit of distortion, and a little bit more character.

The other thing that is great about the M 0.8 glass is that it blends very well with all the other lenses I used. I had the long zoom, the Angenieux Ultra 12x 36-435mm, and the Panavision Panaspeed lenses, as well as two or three different zooms from Panavision. That was my full lens package.

I actually purchased a set of M 0.8 lenses for myself after the film. I fell in love with the form factor; it’s just amazing. Plus the quality of the glass and the fall off… It’s simply fantastic. I’ll carry it in my package on every movie now. I have them on my current series, American Primeval, mostly for all the drone work.

Why did you make the choice to use so many cameras at one time?

The time on the track was very precious to us and we needed to capture as much footage as possible as quickly as possible. These race cars are actually very fragile and they break down very easily with the violence of the speed and the track. You can’t just stop and go, stop and go with them. They have to go all the way around the track each time, and once you do stop them you have to cool them off before you can start them again. And during the race sequences we’re talking about 12-15 cars. It’s quite a lot of steps to make them work and when you stop it’s a huge moment. The use of multiple cameras allowed us to use this limited time to its full potential.

The other benefit was in lighting. From a lighting standpoint, there is very little you can do in this situation except lighting the interior of the car, so getting as many story elements as possible from different angles at the same time keeps the lighting and weather conditions more consistent when editing. We were helped in this way just by shooting in Europe during the fall into winter. This area is very overcast with clouds very low to the ground. I grew up in France and I remember the television broadcast of the races. It was always gray so that helped us stay consistent.

The only races that have a slightly different look to them are in Dubai and Tokyo because those areas have a different, warmer feel. The other tracks we were at are the Nürburgring in Germany, the Slovakia Ring, and the Red Bull Ring in Austria. Regrettably we could not get a permit to shoot at Le Mans so we recreated three sections of it in other locations.

Recreating Le Mans for shooting at night was actually very difficult. The most famous part of Le Mans is the three kilometer long Mulsanne Straight. It’s a road part of the course that goes through the countryside. There is absolutely no light, no lampposts. You are in complete darkness with only the headlights of your car or the cars around you.

We recreated this section on the tarmac of an airfield in Budapest. In the end the section we could do was about one kilometer long. This is one of the very few parts of the film that has some VFX and I needed to give the VFX team some exposure to work with. We ended up lining the tarmac with 14-16 cranes, each with a giant softbox holding about 20 or so Creamsource Vortex fixtures in it. Hiding the light as the actor and car pass through them and balancing the exposure without it looking lit was quite a challenge.

I’m always trying to create the look of a film on set as much as possible. I started with a LUT from Company 3 and then tweaked it a little bit with a German company called Panoptimo. Neill and I wanted something that was somewhat stylish but at the same time not precious. This is a true story and we didn’t want to embellish it. It’s a hard environment and a very difficult journey for this young man. I wanted to give it a hard harshness, some kind of darkness to it, and that’s basically where I went with the LUT that I picked: strong black, strong darks, lots of gray, very raw, very gritty. Yes, it is a coming of age story, but at the same time for this young man in his early 20s going through it so there’s a lot of anxiety as well. My DIT Felix Rauch and I monitored that LUT on set and Colorfront in Budapest who did our dailies applied it. From there it went to Company 3 and Stefan Sonnenfeld who did the grade.

What about the scenes off the track?

There is a certain amount of drama that takes place at the pit and the pit perch where there are cars and trainers and technicians. I used the Panapeed lenses for these scenes. There’s a lot of movement from the trainer Jack Salter, played by David Harbour, who is anxiously waiting for some information so he’s pacing. He goes from the pit perch to inside the communications center. There’s a conversation there before he goes from one pit to another one. Then he goes back and crosses the lane to the pit perch. Meanwhile cars are coming in for refueling and the whole time he’s talking through the comms with Archie’s character who is driving on the track.

Neill wanted to run those scenes like a theatrical play and shoot them in a very continuous way so we did multiple takes of the scene with little tweaks each time, but always shooting the whole thing all the way through. I had five cameras positioned in various places and had to hide lights everywhere in a motivated way to give the option for the characters to be free flowing and constantly moving. We used a longer lens on one camera as he moved from one pit to the other and another camera team would pick him up when he got there. Cameras were hidden in other locations plus we had a drone flying. A driver is coming in for a pit stop so we’re capturing that as well because at the end David has a conversation with the driver. Then Archie comes in and gets in a fight with another driver. And it was all real, no marks, just following the action and seeing where it goes.

Although a lot of it is shot handheld, it's a very smooth handheld. We used a lot of wide shots very close to the actor, always with the environment around, then cut between the very long lens shots, specifically in the action. And of course the drone shots mixed it.

You must have had some pretty good operators.

I had wonderful operators that I knew before from the UK, particularly my A camera operator Tom Wilkinson. I worked with him on two projects before Gran Turismo and he knows my style pretty well. They all did a great job. Neill really wanted the actors to have a sense of freedom to move and react in the scenes so the operators had to be very proactive to find the spot, find the shot, and get the performance.

Overview

DoP Jacques Jouffret

Lens used

M 0.8

Legacy

Unique and small. A new way to look at light, skin and color.